Live

Renovating Folkestone Harbour – A Labour of Love

Renovating Folkestone Harbour has established it as a venue of choice for people living in and visiting the town. Since work began in 2014, civil engineer Ben Boyce has been responsible for project managing many of the renovations undertaken by Folkestone Harbour and Seafront Development Company. Here he speaks with Folkelife about the approach that has been taken to restoring and opening up this important part of Folkestone’s heritage to the public.

folkestone’s harbour area

“I started work here in 2014, and the first job I supervised was the creation of what is now car parking space. At the time, there was a large industrial storage unit on the site, and remnants of the dilapidated ferry terminal building. This linked to an old plastic-enclosed footbridge that was part of the old railway station. We removed the buildings and then laid the surface you see today. This was originally to create a parade ground so that Prince Harry could carry out a military inspection after opening the Step Short Arch, commemorating the centenary of the outbreak of World War I.

“At that time the Harbour Arm was totally derelict. We set out to restore it, making the most of what remained and repurposing elements of it. We wanted to enhance people’s understanding of what had been there and to create new uses for the space. Approaching all our work in a sympathetic way; before we even began, we walked through the site with the local authority officer responsible for conservation. It was important to get this right.”

Folkestone Harbour’s resilience

The Harbour Arm is constructed of concrete faced with granite. Although the construction has been fairly resilient over more than a century, standing up to ferocious storms, it certainly hasn’t proved to be bomb proof. Ben and his team found evidence of shrapnel damage and bent pieces of metal scattered around the site. Nevertheless, the granite itself is robust: “We’ve shot-blasted it to clean it, but it doesn’t change the stone itself, which remains incredibly solid.”

There has been similar effort to mark and record other aspects of the Harbour Arm’s history. Along the upper level, for example, a metal rail was found to be embedded in the granite wall, part of a mechanism that supported giant gantry cranes moving the length of the Harbour Arm. Ben says: “On inspection, we found that this metal rail had rusted badly in salty conditions and the resultant corrosion was effectively bursting open the granite, risking the structural integrity of the wall.”

industrial history

“It was decided to replace the granite like for like, rather than with concrete, as had been done under previous ownership. Then we inlaid new rust-coloured granite down the middle of the wall. The effect of this has been to mark the previous line of the rail whilst eliminating the risk of corrosion. It allows visitors a glimpse into the industrial history of the site.”

Meticulous attention to detail has been afforded to every element of the restoration, as well as the overall design of the space. Ben adds: “For example, the post-and-chain fencing has a heritage ‘feel’ to it; it is made from cast metal, like the posts would have originally been. It is an active harbour so we needed to use removeable chains as opposed to solid railings. This affords some protection whilst maintaining the potential for boats to moor alongside.”

Restored with history in mind

Ben’s role at Folkestone has enabled him to explore his passion for investigating the past. “If you walk along the Harbour Arm there are two mesh platforms which sit above really interesting spaces. Folkestone has a seven-metre tidal range, and these docking areas are a consequence of that; they provided a place where boats could be loaded and unloaded at low tide.

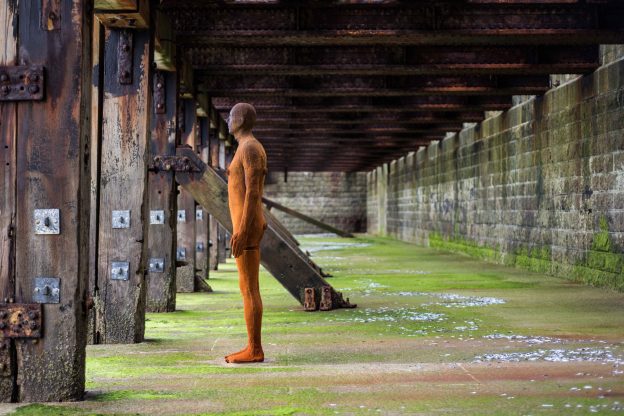

“In the past, the lower landing closest to the Lighthouse had two staircases. Port workers could walk down and board or unload from the boats. We’ve excavated the steps to the larger docking area, which is now home to one of Antony Gormley’s cast iron figures, first displayed as part of the 2017 Folkestone Triennial. Viewing this work from different vantage points gives visitors a feel for the space: it’s particularly magical when the tide is almost at the same level as the dock. This area also had a ramp which was primarily used to allow access for horses to and from ships, particularly in the First World War. The Harbour’s history during WWI is fascinating; it was commandeered by the War Office for a period and was used as a port for war operations.”

war memorabilia

Ben relates that numerous artefacts and original features have been discovered during the repairs and restoration: “I get excited by the little details we’ve found; for example we’ve removed timbers to find a button from a military jacket or pieces of memorabilia, all helping to add to our understanding of the history. We’ve tried to repurpose everything where possible, and to uncover features that in some cases had been hidden. In the corridor rooms, for example, we have revealed and restored original fireplaces.”

Ongoing MAINTENANCE

When more substantial maintenance is needed this is generally done in the winter months where possible, to cause minimal disruption. Over winter 2018/19, for example, two large awnings were erected over a large part of the Harbour Arm to enable the area to be sandblasted and painting to take place. Ben explains: “The tented area needed to be heated, as the paint had to be applied at temperatures above 20° C. Ideally, we should do this during the summer, but this would reduce access to the space during the high season. During the coronavirus lockdown we were able to do a lot of spring cleaning while the area was quiet. ”

Challenging conditions

Ben explains that the metal on the Harbour presents one of the most challenging issues for maintenance. “This is an incredibly aggressive environment: we get over-topping waves as well as almost constant salt air and spray. If you run your hand under the under the railings you’ll get a coating of salt on them. Some of the canopy structure was so far decayed that we’ve actually replaced it rather than repaired it. Although it has been done so sympathetically that people would be hard pushed to tell the difference. The paint system we use is designed to last fifteen years, but in practice we need to inspect it annually and renew where necessary to make it last that long.”

Discovering the past

Renovating Folkestone’s Harbour revealed some surprises, as is often the case in projects like these. Whilst working on the enclosed area known as the “mid-rooms”, Ben and his team found evidence of an old platform about 2 metres further back from the current platform edge. “There were signs that the original curve through the middle section used to be a lot tighter. It is possible that trains couldn’t negotiate the curve, so it was rebuilt to make it more gradual. A new platform was constructed along the line of the new curve but the old one was clearly left in place.”

“We also found a large area that had been used as toilets, close to the site of the former Mole Café. This was where troops were fed and watered as they passed through the port during World War I. When we removed the decaying render, we found glazed tiles beneath, many of which had been smashed over the years in order to hold the render in place. It represents an important detail of the history of the Harbour.”

Harbour work continues

“There is still plenty to do,” Ben continues. “For example, some of the historic brickwork in the Inner Harbour is in a poor state, so that needs work.

“Richard Taylor, of “Nik and Trick” Photography in the Old High Street, has been commissioned to make a photographic record of the progress made as things develop. Richard’s father was a photographer on a local newspaper, and we have access to his very extensive archive. We’re also working with local historians to build a digital record of the site’s history. This has helped to inform decisions we have taken about the restoration.”

Ben’s interest in the history of the harbour is wide ranging. He continues “It cost a fortune to build the Harbour but actually it was not a great success. The Arm (variously called “New Pier” and “Mole”) provides protection from the prevailing winds. However, because the water doesn’t flow fast here, the sea bed silts up very quickly. When the ferries were operating, it needed to be dredged fairly constantly. It made it more expensive to operate than, say, Dover, which also has fewer tidal restrictions. When duty-free shopping ended, the commercial case for keeping Folkestone open was seriously undermined. Of course, Eurotunnel opened in 1994, marking the advent of a brand-new route to and from the continent. The ferry port closed, at around the time of the millennium, there were some who suggested that it might re-open to traffic. Despite years of discussions with potential ferry operators, none came close to proposing a viable operation.”

Future of Folkestone Harbour

The Harbour Arm’s repair and new purpose have only been possible through significant investment from Folkestone Harbour General Partnership Ltd. This is the organisation responsible for the development of the wider harbour and seafront area. Going forward, maintenance of the areas open to public and the Harbour itself will be funded through revenues generated from this wider development. This should ensure that the Harbour and Station do not fall into disrepair as in the past. This investment is safeguarding an important part of Folkestone’s heritage for the future. This means that residents and visitors will continue to enjoy what has become one of the town’s most popular attractions.

Ben is enthusiastic about the legacy that these developments have created: “It’s all there, for future generations to see; they can see we’ve maintained this space, without erasing the history. For example, if we had replaced the old railway enamel signs with plastic ones, it just wouldn’t have been right. People can see we’re planning for this to last at least another 100 years. With proper maintenance, it will be here for a jolly long time!”